We are big fans of Avinash Kaushik, so when his article ‘Brilliant Brand Measurement’ started making the rounds, we were frankly excited to see what he had to say about evaluating the success of brand marketing.

On the whole, he put together a pretty great framework for brand measurement featuring well-defined signals that will absolutely help marketers better understand how their brand marketing initiatives are actually performing.

But our favorite thing about Kaushik’s article is the conversations it generated, which started happening internally on Slack, over email, and in meetings almost immediately. So we decided to give you a sneak peek into some of the conclusions, thought starters, and even points of disagreement we heard from our experts.

To help you get a handle on your own approach to brand measurement, we’re going to zero in on the second section of Kaushik’s article and focus on three things:

- Brand marketing outcomes and problems to solve

- Impact horizons for brand campaigns

- Brand measurement dos and don’ts

Oh, and if you weren’t sure whether or not you should sign up for Kaushik’s The Marketing<>Analytics Newsletter, you should. It’s one of the best sources of industry intelligence out there.

Establish the business outcomes you want to drive with brand marketing

Kaushik asserts that four long-term, not-easily-solved business outcomes actually cover the entire breadth and depth of what brand marketing is trying to accomplish:

- Unaided Awareness

- Consideration

- Purchase Intent

- Image

We mostly agree with those buckets, but we found some flaws in his critiques of two additional options brand marketers often point to as important outcomes and metrics.

The first is Aided Awareness. Kaushik despises it as a potential metric because of how easy it is to move, since it’s based on a prompt, and how quickly it decays, making it more difficult to tie to business outcomes.

It may be all well and good for established brands to bypass Aided Awareness, but it’s an essential metric for smaller or newer brands trying to move into a market, especially in verticals where there are entrenched power players.

“If one is interested in a minor or starting brand, its aided awareness will be more sensitive, and therefore more able to detect progress in the brand’s awareness.”

For those brands, Unaided Awareness will be extremely tough to measure in a field crowded with more established competitors. Aided Awareness might function as a vanity metric for those bigger brands, but it’s important for less mature brands to understand what’s making an impact as they work their way into the arena.

The second outcome/metric Kaushik flags as a pet peeve is brand love.

“It is not uncommon for your Research Partners, Agencies, CxOs to poist additional purposes like “Brand Love.” Ironically, I’ve come to not love these “metrics.” First, they mean nothing. Second, they mean everything. Third, they mean anything. Fourth, they can change with the seasons.”

We understand the frustration with a strict definition of brand love, but it’s also more than just a vanity metric. How do we know? Because it produces business outcomes. Brand love is the source of advocacy and evangelism, and there’s no better acquisition engine than the endorsement of current customers.

Brand love is a byproduct of brand image; love isn’t limited to your existing customers, it can spring from admiration of a brand mission, how your business solved a critical marketplace need, or an aspirational wish to become a customer someday.

But it’s only useful if you can measure it; in fact, we suspect that the inconsistency in how brands measure brand love is the root of why it’s so easily dismissed. We suggest considering something like brand salience to fill in the gap.

According to recent research from Romaniuk and Sharp published in the academic journal Marketing Theory, “brand salience defines the brands’ ability to stand out in memory during purchasing decisions, not just to be recalled.”

Memory isn’t enough to equal brand love, but if we look to understand how engaged consumers are with that memory, it’s getting us a lot closer. Measuring brand salience takes some work; the metric is based on a range of cues likely to influence buyers making purchase decisions specific to the industry or category (i.e. service, price, quality, etc.)

Measuring the success of brand marketing campaigns against specific challenges

Kaushik then pivots to talking about the specific problems a given campaign is trying to solve. After all, one campaign can’t solve for everything; too many brand marketing campaigns throw all of the balls in the air at the same time and end up doing a mediocre job instead of zeroing in on one outcome and doing everything possible to achieve it.

In the end, you need to pick one thing you want to accomplish to be successful.

“[S]adly you can only solve one problem at a time (it really is that hard). If a human says [both] Consideration and Image, this human has never run a successful brand marketing campaign – or has never been blessed with an accurate measurement of their campaign, and hence is oblivious to the truth.”

We love this framing around decision-making based on outcomes, but it fails to recognize the biggest problem brand marketers face, which often leads them to try to accomplish multiple outcomes: which challenge should they target?

Since we agree that brand marketing goals should be rooted in addressing a challenge, marketing leaders should create campaign objectives in tandem with a corresponding hypothesis a particular campaign can test or even solve, informed by the core business objectives and key brand challenges. That’s where finding the “how” begins.

Some brands utilize historical brand tracker results to inform their measurement objectives, starting an analysis of how they stack up against the competition in key brand health metrics. If your brand is lagging in awareness versus competitors, but winning in consideration and image, that gives you some important insights that can inform campaign prioritization and narrow the brand messaging focus.

Let’s take a look at how this process would work for an imaginary brand. We’ll call this brand DBCP (Dinosaur Brand, Cool Product):

- The basics: DBCP’s north star business objective is to drive revenue, and the associated core marketing objective is new customer acquisition

- The challenge: DBCP’s core audience is still valuable, but they’re aging. To drive longer-term sustainable growth and set up the business for future success, they need to start reaching a younger demographic. So how does brand marketing help?

- The solution: Even though the end state goal is to get this younger audience to buy, that won’t happen overnight because these younger consumers don’t know anything about DBCP; they know from that competitive analysis of key brand health metrics that they’re not even on this younger audience’s radar. That means brand awareness is a great first objective for brand marketing to tackle before anything else.

Once you’ve identified the right brand marketing objectives, you need to figure out which angle to take in your campaign:

- Brand essence

- Value proposition

- The brand’s mission

- Point of difference

You should continuously test campaigns that focus on different attributes and assets as solutions to the outlined brand challenge to understand what resonates with your target audience, as well as ensure you’re keeping your creative fresh to maintain relevance over time.

The holy grail everyone is looking for is how to unlock the relationship between brand metrics and downstream revenue impact. But not all brands have the luxury of clean, historical data in order to inform their planning objectives, and even brands who do everything right will likely find it challenging because of the limited nature of brand marketing data. We have an entire Marketing Science team dedicated to this type of analysis and tasked with creating benchmarks to inform future campaigns for our clients.

Defining the “impact horizon” for brand marketing initiatives

Kaushik also points to a common pain point associated with brand marketing campaigns, especially for brands acclimatized to the quick-win nature of traditional performance media: patience.

He rightly points out that each brand marketing outcome has an associated impact horizon: the time you can expect to wait to see the impact of a brand marketing campaign on the business itself.

Think about it this way: let’s say you need a car to get around. Consumers buy a new car on average every six years, but in that time frame, long before actually the idea of buying a new car is even a meaningful twinkle in your eye, you’re going to see a lot of advertising about cars.

The purpose of most of those ads, in particular the big national campaigns you see on TV, in a magazine, or on a billboard, is to drive awareness, image, and, yes, brand love (sorry, Avinash!). Once you decide to buy a car, those brands are hoping they’ve earned a spot in your consideration set.

What should be immediately clear from this example is how long it can take for these upper-funnel brand campaigns to bear fruit. Cars are a major expense and ideally last a long time, so they’re going to be on the high end of the timeline. But all brand marketing campaigns, across all industries, have an impact horizon.

Kaushik then posits that each brand marketing outcome has a different impact horizon, and the higher it is in the funnel, the longer that impact horizon gets:

- Purchase Intent: 180 days horizon

- Consideration: 9-12 months-ish

- Unaided Awareness: 15-24 months-ish

- Image: 2-5 years

None of those windows is set in stone; Kaushik notes that the impact horizon for purchase intent could be significantly shorter if the project is at a low enough price point, and brands investing in building a resilient brand image are generally much more established and willing to make a very long-term investment to get a huge and lasting payoff if the campaign works the way it’s supposed to.

But although this sounds fairly neat and tidy, it’s not always possible to define the impact horizon prior to launching the brand campaign, and we know firsthand that it can be an uphill battle. Conceptually, Kaushik’s guidelines make sense and are helpful to set some level of expectations with brands used to a much shorter turnaround on ROI, but most marketing teams don’t have the luxury of a wait-and-see approach, especially when there’s a big investment at play or if brand marketing is net new.

Even the general windows he provided will differ heavily based on other factors he doesn’t mention, particularly industry saturation and competitor spend.

The key is to set realistic expectations and start cultivating a level of patience that will be uncomfortable at first if the brand is new to this kind of marketing.

For socially and digitally native brands, the impact horizon of even upper funnel campaigns on those channels could be a matter of seconds, minutes, or hours if you have your credit card loaded up to Instagram, particularly on the lower end of the price point. Marketers should use in-market signals like social proof to make the most of those platforms’ power to introduce your brand effectively to new audiences.

The movement to more in-platform transactionality has made it possible to make the journey from discovery to conversion faster and more seamless than ever, but it doesn’t completely solve for longer-term research and consideration phases, which are more and more common in the current economy. Traditional brand marketing with higher impact windows is built to help get your brand into the consideration set before people are even considering a purchase.

Building an effective measurement framework to understand brand performance

Kaushik lays out four important questions marketing teams should be able to answer to build better, more measurable brand marketing campaigns:

- What brand marketing problem is the campaign solving?

- Is that problem worth solving?

- Is the advertising creative solving for the problem worth solving?

- Do you have enough media budget behind the creative?

Once you’ve answered those questions, you can start drawing the line between the intended campaign outcomes and how you’re measuring success. Brand measurement objectives should be dynamic and account for the maturity of the brand and where it is in its growth trajectory.

As a brand matures, new needs will arise, like new customer expansion, product evolution, and repositioning for cultural relevance. Those changes can require a fresh approach to your brand marketing campaigns and associated objectives and KPIs.

There’s no universally accepted, strict linear progression of brand measurement KPIs to follow based on brand maturity; instead, they need to be rooted in your marketing objectives, which are of course subject to change as business objectives evolve over time or new challenges arise. Those challenges can be acute and require immediate attention (inflation is affecting consumer purchasing behavior) or longer-term and even existential (our audience is aging and we need to start recruiting a younger customer cohort).

Teams need to define relevant directional indicators of success to monitor how the KPIs they’ve chosen actually perform against the desired outcome of a campaign. Simply put: your brand marketing KPIs should have KPIs. That’s the only way brand marketing investment can be accountable, which is a requirement for today’s marketing teams.

To make that happen and keep things organized when we manage brand marketing campaigns for our clients, we create a robust measurement framework to track leading and lagging indicators over different time horizons and understand the impact of that media on total business results.

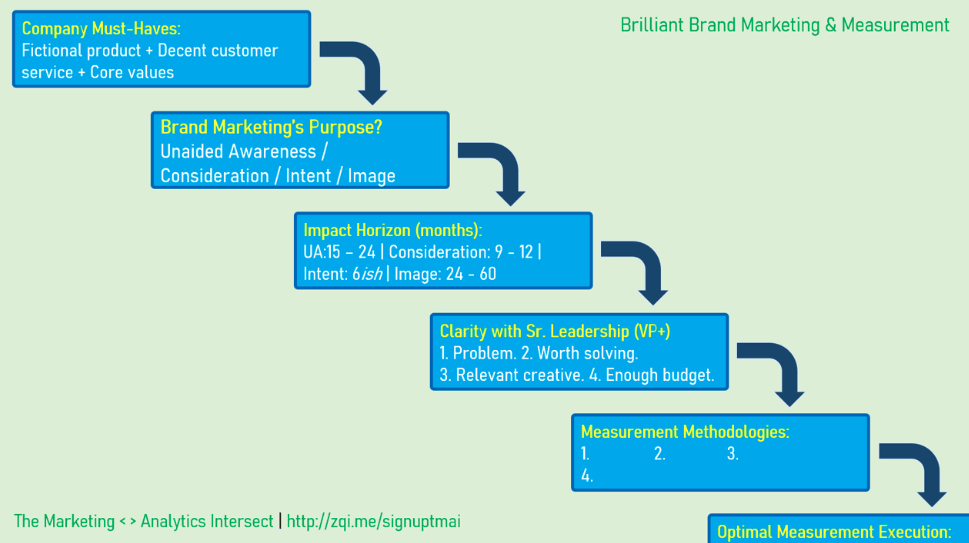

Kaushik shared his version of a brand marketing waterfall that you should find particularly helpful because it shows how all of these prerequisites feed into each other and set your brand up for long-term success.

We know brand marketing is difficult because there are so many variables at play, but it is possible to build your brand while holding your investment accountable.

Responses